In September, I wrote about our friend Emmanuel the school teacher; about his life and his ambitions. We used the opportunity to fundraise so he can complete a two year primary teaching qualification. This will enable him to earn a better salary as a qualified teacher and support his family.

Our aim was to raise KSH234,500 – around £1,800 – divided into money for the course and money for his family (to make up for his lost earnings). Emmanuel applied to his local church for assistance, and the ‘Men at Work’ group agreed, at the last minute, to sponsor 75% of his first year fees. This means we need to raise KSH191,875 – or £1,475. We have so far raised £1330, so only need to raise a further £145. Please email reyindia@hotmail.com if you’d still like to donate!

Emmanuel started school in September, and the first year’s fees and other expenses are now paid. We see him every month, as he comes to say hello and to collect the maintenance grant for his family. Thanks so much to all of you who donated, enabling this to happen; it is really appreciated by us, and more importantly, by Emmanuel. In his own words…

I greet you in Jesus name, this is Emmanuel Mutiso. Let me begin by saying a very big thank you for responding to my request. May the Lord abundantly bless you indeed.

I have enrolled for my Teacher Training Course at the International Teaching and Training College, pursuing a Primary Teachers Certificate. On the first day, after meeting the Principle, he took me to the Bursar, who loaded my name into the computer, and then I became a full student of the school. From there, I was taken to the dorm and given a bed and I took my things there. Because I started a little late, that first evening I began writing notes and acquainting myself with what the other students had already been studying. I got hold of the pamphlet for Theory of Social Ethics and read this a bit. In the morning, I started my actual classes.

The structure of the two year course involves six semesters (three a year). This semester we are the students and next semester we are the teachers, or at least doing teaching practice. Then it’s back to the classroom for the third semester, teaching practice for the fourth, and so on. At the end we will take the Kenya National Exam for Primary Teachers, although there are other smaller exams at the end of the semesters. We are just finishing the first semester, and have started our first set of exams, and then we will go out to the schools we have been selected to go to. After coming back from the December holiday, we will arrange the lesson plans, then we will go to the schools and begin the teaching practice.

When I first came to the college in September, I felt so happy, I felt encouraged, I felt like I was moving on somewhere. After I finish, I desire to pursue a degree in the same career, for I am passionate about it. The Primary Teachers Training Course will take only two years after which I desire to advance to Kenyatta University or Nairobi University or Moi University and pursue a degree in teaching Biology and Chemistry at Secondary School.

But when I started, I was worried a little bit because of the situation of my family at home – because I had to leave work, and my brother was still in school. That was my point of worry – how they were going to meet their daily needs.

But at home now, mum is fine and our last born brother Peter has just cleared Form Four (Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education – KCSE). His results will be out next year in the last week of February. We do pray that all shall be well. May God bless you and keep you, may He course His face to shine upon you. I hope to hear from you soon.

Yours faithfully,

Emmanuel Mutiso.

Posted in church, slums | Leave a Comment »

When mother saw me off on my first trip to Africa in 2007, there was definite finality in her wave. When she found out I’d broken a toe two weeks in, that settled the matter: I was coming home in a coffin. Everywhere else was fine – but there was something about this continent which terrified her.

To some extent, who could blame her, when stories about Africa which reach the West are invariably negative? Britons have recently read about slum fires, two kidnappings and famine in Kenya alone. So when I insisted mother put the Daily Mail DOWN and come visit me, she was reluctant and downright scared. But I deemed it essential that my own mother experience what it’s really like in a developing country and what I’m doing here, in the hope that she would accept my decision to volunteer and – more importantly – return home with a more informed attitude towards Africa.

And when she came through arrivals looking like Joan Collins and armed with neckerchiefs – But Beeba, I thought everyone in Africa wore neckerchiefs? – I saw a bit of the old me in her. First the trepidation, entering the unknown – and then seeing Kenya first-hand, interacting with its people, and realising what an amazing country it is. I’d like to share her learnings with you. Because if mother can return home raving about Africa to Mike the Plumber, anyone can.

A qualification. Mother is highly intelligent. She is a businesswoman (the driving force behind Hertfordshire’s first dating agency, the family restaurant and Tankerfield House B&B). She is also academic, having recently been awarded a First Class Honours in Literature, and her short stories come commended in writing competitions. However, when she is out of her comfort zone, she morphs into the human equivalent of the wildebeest; a species which roams the Maasai Mara in its millions and whose sole reason for existence appears to be to provide food for the rest of the animals. So forgive her her transgressions; she was on a steep learning curve.

1. Bewilderment

Mother’s level of comprehension throughout her trip was, by her own admission, very low. I would try to reduce her dependence on me by frequent tests (Where are we now? Watiamer? No, Watamu. How did we get to Mombasa? I have no idea! Did we fly?). But I knew I was flogging a dead horse when I asked what she’d do if we separated. She frowned, thought a bit, then announced: I would go to hospital and ask for Tom! (The fact that there are many hospitals in Nairobi and Tom researches in a small section of one, thus making the likelihood of us ever being reunited slim to none, made me feel alarmed, and yet…intrigued).

Kenya was such an assault on the senses that mother lost it. Where are we, Beeba? Nigeria? On safari in the Maasai Mara we saw everything from elephants to lions to leopards. But mother was pouting – Where are all the tigers, then?

Mother’s bewilderment had practical consequences. For twelve days, she forgot the function of a light, toilet, shower and kettle. She got flustered in the safari van (How does this seatbelt work? It’s like an aeroplane seatbelt. But I’ve never been on an aeroplane! Mother, you flew here in one). Neither could she open the door, despite its simple sliding mechanism. So when a giant baboon jumped through the front window, it was like the kitchen scene from Jurassic Park, with mother pulling at the door and screaming for our absent guide (whom she never forgave: Text Tom EVERY movement while we’re on this safari, she demanded. I think George wants us dead).

But slowly, bewilderment turned to appreciation. Everything was new and she walked about wide-eyed, absorbing things like a sponge. Have you ever seen a giant cactus? one guide asked. NO! A tree hyrax? NO! She saw good in everything and everyone – to a fault, especially in the restaurant where she shouted: Look at the safety lines painted on that step! Aren’t they STUNNING? (Admittedly, she’d gone overboard on tequila and a minute later inexplicably started weeping with laughter). On the first night, eyes glazed with the excitement of it all, she declared: Beeba, I’ve had a wonderful holiday.

2. Misunderstandings

Just as kettles work the same as in England, so are the people still people, living in the twenty-first century, trying to get by. Someone forgot to tell mother. Why don’t they build mud huts in Nairobi? she asked Tom’s (very understanding) Kenyan friends. She was in her element with our neighbours on the Rift Valley Railway; an Australian pair who gave the history of the famous white settler Karen Blixen which turned out to be a summary of the plot to Out of Africa starring Meryl Streep. The three soon moved onto more controversial topics: health (Results from blood tests are very fast here; you wouldn’t expect that of Africa), education (Don’t they all sit cross-legged under a tree to learn?) and youth (Black children are so sweet! Oh, look at this ugly one).

Whenever engaging with Kenyans, my services as a translator were required. It reminded me of the time my friend Craig’s mother visited – from Yorkshire. I don’t have much trouble understanding the Kenyan accent now, but watching mother in conversation – My name is Humphrey Kamau. Oh hello, Amfrickamo! – would leave me cringing. I was texting in a café one lunchtime while she chatted with the owner. When his back was turned, she poked me in the ribs and hissed, Aurelia, I NEED YOU! I don’t know what he’s talking about!

But mother was quick to shed her preconceptions (if not her misunderstandings), and launch into interactions. She talked to EVERYONE. She chirped Jumbo! to each person passing us on a fifteen minute walk through one village. She entertained the beach boys and asked the Maasai guards about their culture. She promised to send Indiana Jones to one guide after she told him about the monkey stew (alright for her, I had to traipse around town looking for it, then endure a stint at the post office). At every turn, she wanted to learn.

3. Mistrust in transport

I long ago gave myself up to Kenyan drivers, putting my faith in their unorthodox behaviour and abilities. But I saw through fresh eyes how counterintuitive it seems that taxi drivers, tuk tuks and matatus wait for you to board and THEN fill up with petrol. I saw that it might be disconcerting when the matatu shudders to a halt in the middle of nowhere and the driver starts fiddling under the vehicle before calling Mohammed to ask Where’s that switch you were telling me about? And equally alarming when the taxi conks out three times on a busy highway, and each time the driver leaps out and starts poking things under the bonnet with a bemused expression.

Yet mother transformed into master of getting-on-with-it. She became patient for the first time: sitting in the notorious Nairobi jam for an hour without complaint, throwing herself onto every manner of crowded public transport, insisting on carrying loads on her lap, helping women into seats and starting a round of applause after a bus driver took an hour to change a tyre. Although she drew the line at a piki piki, by the end she dismissed my suggestion that we get a taxi to her final meal and hailed a matatu like a local.

4. To give or not to give?

I don’t want to be glib here. The poverty hit mother hard. When we saw a man stripped to the chest, barefoot, sweating as he dragged a wooden cart laden with drums of water, she was horrified. But how to deal with our wealth was one area where we just couldn’t agree. Everything I’ve tried to finely balance since arriving – insisting on paying the same as everyone else on the matatu, not giving street children money in the belief it might encourage them to skip school, paying a fair price for souvenirs (not too high, but still above the local rate) – departed with mother’s arrival. Here for a short holiday, she wanted to do everything she could to help. And she had no concept of context: £1 here does not translate to £1 in England. The tuk tuk driver wanting 100 bob (80p) instead of the usual 50? Give him 150! The taxi driver charging 700 bob (£6) instead of 500? Give him a tip too!

I constantly swatted her away. Worst of all was buying souvenirs. When women surrounded us on safari, she selected eight bangles and instructed: Pay whatever they’re asking! And even when she tried to haggle, she got it wrong. I was negotiating with a shop owner over some prints when she interjected assertively, I’m not paying more than £30! Tell him I’m not paying more than £30!! MOTHER, I snarled after my shushing was ignored, He’s not even ASKING for £30! So it’s a good thing that I’m a total control freak; I held the purse strings throughout and inflated conversions where necessary.

The parting

I’m fed up of Europe, Beeba. I’m an African now, mother declared halfway through her visit. By the end, she finally understood what I was doing here and why I love it. I was thrilled: mission accomplished. Still, when she turned to me on our last day and pleaded, eyes glittering, Can I come out again, Beeba?, I nearly burst into tears. And her parting words reassured me that she was still the same Mumma: These Africans, they’re very peaceful, aren’t they? Noone’s tried to spear us or anything. I waved her through departures wearing a Masaai shuka, eight bangles and a straw bonnet. Then I went home and slept for two days.

Posted in haggling, masaai, matatus, mzungu, railway, slums, the coast, traffic | 7 Comments »

6 December update: so far we have raised £1230. We are 83% there! Thanks so much to those of you who have, or have pledge to, donate. Every penny/cent/shilling helps! Emmanuel has started school – I’ll update you on his progress.

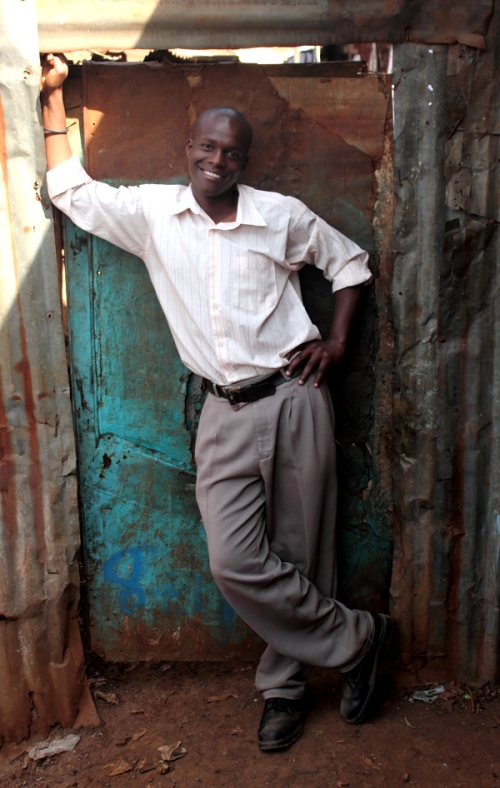

Emmanuel was met through a friend. He comes to our house to help Tom practice speaking Swahili, but has taught us both a lot about life in Kenya. He’s told us stories about living in Kibera, the infamous ‘largest slum in Africa’. His favourite is the tale of the three robbers who plundered a grave and drove off with its empty coffin. The police were tipped off and gave chase; two men were shot dead and the third climbed into the empty coffin, praying that if he survived he would devote himself to God. The police looked thorough the coffin’s Perspex paneling and were horrified to see a dead man. While they were deciding what to do, the dead man leaped out of the coffin and ran for his life. The police and onlookers ran, too – in the opposite direction, so terrified were they at his reincarnation. The dead man confessed the next day, was let off by the traumatised police, and is now a popular preacher.

Such tales are not so bizarre to Emmanuel; having lived in Kibera all his life, he understands the desperation of people, the lack of stable employment, and the necessity of struggling by whatever means possible to earn enough to eat. Emmanuel is unrelentingly positive, charming and fun, but he also has high aspirations. He’s currently an unqualified teacher, but Tom and I, along with some members of his church, are paying for him to complete a two year primary education qualification. It’s expensive but it will improve his family’s life dramatically, as he will be on a much better salary. We wanted to write about Emmanuel and see if anyone wanted to join us in helping him.

Emmanuel is 27. His Tanzanian father left him and his siblings when he was young, returning to his homeland and favoured first wife. Emmanuel’s mother – his father’s second wife – raised the children alone, feeding them with the money from sporadic cleaning jobs, but she fell ill. At 16, Emmanuel was forced to drop out of school to look for work, doing anything and everything that brought home a few shillings. He joined a dancing group which entertained at weddings for KSH400 a time (£3); found casual work at a water park, walking the 1 ½ hours each way to save money on the bus fare so as not to dent his KSH250 (£2) a day fee; and rose at 5am some days to sell charcoal for KSH50 (35p). At the end of each day, the most he could hope for was enough money to buy ugali and sukuma wiki for his family’s daily meal.

Emmanuel recounted this time to us in a matter-of-fact tone. He is not bitter or hardened, and nor does he show any regret for the jobs he had to do. Any discouragement was dampened by the thought of his younger brother and the desire to keep him in school where he could not be. And crucially, his faith sustained him, for Christianity plays a huge role in his life. A tall, open-faced gazelle, he bounds into our house with cries of ‘Hallelujah!’ most weekdays. He is heavily involved in his church’s outreach activities, visiting hospitals, schools and other churches to talk to people not just about Christianity, but about other issues such as HIV/AIDS and the dangers of drugs.

Emmanuel told us that his eldest siblings were killed by his father’s first wife, a witch who practiced black magic on them. The eldest died of an eye disease shortly after the wife told his mother she would bury him. The second died after becoming involved with a scarlet woman: one day, their neighbours witnessed smoke in the hut they shared. They forced open the door, put out the fire, and found Emmanuel’s brother bound by his hands, feet and waist to the wall. The girlfriend disappeared and the police refused to get involved; these are not uncommon occurrences in Kenya’s slums.

Emmanuel’s huge positivity, determination and charm led him, a year after leaving school, to a Kenyan working for an NGO. The man heard his story and took him back to school, paying his fees and buying his uniform. This was the start of a small reversal in fortunes, although his inability to earn money meant that his family sometimes ate nothing all day except when provided by neighbours, and forced his mother, not yet recovered from her illness, to seek work again. Emmanuel had to share a pair of shoes with his eldest brother; in the day, he would wear them to school, and in the evening his brother would wear them to his job as a poorly-paid night guard.

Emmanuel finally finished school in 2006 at the age of 21, but was soon back on casual jobs to keep his brother in school. He experienced a small bout of luck again when his former teacher, seeing his passion for teaching, connected him with a school, where he now teaches biology and chemistry. However, with no teaching qualification, he is bound to this job; he would not be able to find another school willing to take him on without a certificate. But his KSH5,000 a month salary (£42) is at least a stable income, and he can afford to cook ugali and sukuma wiki each day.

It’s hard to imagine Emmanuel’s life. Visiting his home in Kibera is a shock. One must climb over open sewage ditches and strewn rubbish and there are children playing about unsupervised among it all. Rent is cheap by our standards, ranging from KSH800 to KSH2000 (£6 – £16) a month, depending on whether it has a corrugated iron roof and cemented walls or is simply a mud hut – but not when you consider that each home is usually one room comprising a bed, two cooking pots and a stool. If you have the money, you can hook up electricity for KSH300 (£2.40) a month; when we visited one evening, the neighbours were watching the scourge of Kenyan TV, a Mexican soap opera. But there is very little stability or incentive to invest in homes beyond this; the Government, which owns all the land in Kibera, doesn’t recognise the slum as a valid settlement, and has the power to destroy homes at any time.

But Emmanuel has lived here his whole life. He says he’s used to the instability, the rubbish, the smell, the overcrowding. He even claims it is better than it was when he was growing up, even though it is more crowded. It is cleaner now; there were no drainage systems to be seen back then. People are more educated: while many are still illiterate, the introduction of free primary education in 2003 has meant that most young people now have at least a basic education, although often of dubious quality. The rise of NGOs, disparaged by so many, has enormously helped those they target; Emmanuel is testament to that, as he was given a second chance at school.

In a country where people have traditionally seen cities only as places of work, owning ‘real’ homes in the rural areas of their tribal community, Emmanuel is one of many young people today who has only ever known the slum. He dreams to own a plot of land where he can build a house for his mother to retire. In the meantime, he has ambitions; if he could become a qualified teacher, he could encourage more lives through education and help slum children go through what he went through, at the same time as supporting his family.

Emmanuel is hardworking and believes that ‘so long as God gives us grace and gives us hands, we can work’. Tom and I hope that we can help him achieve his ambitions, and we’d love it if you could help us help him. The fees are quite expensive, and we also want to give a small amount of money each month to his family to make up for the lost income they would otherwise feel by his absence. We know Emmanuel, and we know it will help his family, a lot –and living in Kenya, where every day you have to walk past someone you could help, it feels like we will have made a positive difference in some small way.

Please email me: reyindia@hotmail.com. Every penny will go direct to him and his family.

Details

We are trying to raise KSH234,500 – around £1800. This is divided into money for the course, and money for his family (to make up for his lost earnings). All money in Kenya Shillings (using a rate of £1= KSH130. It’s currently around 145, but it fluctuates a lot and we want to make sure we’re not short).

1. The Primary Teacher Education Course (PTE) is at the International Teaching and Training Centre in Nairobi. It is a two year course.

Registration fee – 500 (first year only)

Bus maintenance – 600

Medical Fee – 900

Activity Fee – 1,500

Tuition and Boarding – 54,000

Total: 114,500 (57,500 year 1; 57,000 year 2) – or £880

2. We want to give KSH5,000 a month to his family, so they don’t feel his absence financially. This is only £38 a month and you could argue that we should give more, but our aim is not to support Emmanuel’s family; it’s to help Emmanuel support his own family.

Total: 120,000 (60,000 a year) – or £923

We would be grateful to receive money in any form you are able, and as little (or as much!) as you can afford. It could be a lump sum, or monthly installments over the two years. We can pay the College in installments, and it is easy for us to send the money direct to his mobile phone from England. reyindia@hotmail.com

Posted in slums | 3 Comments »

I like to classify myself an ‘Adventure Traveller’. Not for me an Overland truck where you book up, climb in and get driven. No; all I need is my guide book, and only then to tell me where all the tourists flock, so I can avoid it. Intrepid? I think so. Snobby? Definitely.

The problem is I am, in my brother’s words, ‘completely impractical’. I’ve cycled from Land’s End to John O’Groats but I still can’t repair a puncture (This bit, a freezing cold Orlando snarled as I hopped about, is NOT ‘a wiggly worm’). I’ve camped in the Andes, the Rockies and the Rift Valley but I still can’t put up a tent (Aurelia….my friend Lucy hazarded at a campsite in West Sussex, I think that’s inside out). I’ve interrailed across Eastern Europe but I still can’t read a train timetable (I’m not sure this definitely is the right way, my companion Spain turned to me after three hours clattering through Romania – The sea…isn’t it on the wrong side?)

So woe betide anyone who entrusts their well-earned holiday to me.

My obsession with ‘doing things differently’ has unwittingly led friends into traps before, normally provoked by my fateful entreaty, Come on, it’ll be fun! A day-long thunderstorm in Budapest spent on a bus wasn’t quite as romantic as the movies would have you believe, an impromptu four hour hike in the Tuscan mountains nearly lost me my best friend and after driving aimlessly for two hours around northern France at night, my friends moaned that ANY campsite will do, and didn’t you do ANY research? We’ll laugh about this one day seems to be a stock phrase of mine.

But there’s nothing like actually living abroad and spending Toothbrush Time gazing at a map of the country to provoke one’s appetite for adventure. And, days, weeks or even months later, to set forth upon that imagined adventure, and watch helplessly as it unravels…

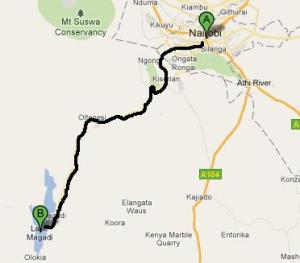

Lake Magadi: Mercury Rising

The guide book describes the environs of Lake Magadi, the most southerly of the Rift Valley lakes, as ‘a remote, lurid inferno’. Come on! I persuaded Tom, Let’s do a day trip. It’ll be fun!

We hired a Land Rover Defender, I stalled it and then hit a bus. Two hours of fingers-over-eyes from Tom later (cursing the day he let his driving license expire), we approached Olorgasailie Prehistoric Site. I read about this, I said, remembering something about the Leakeys and archaeological discoveries. We ought to stop, I insisted, and roared into the compound. As we alighted, Ennio Morricone’s Wild West refrain whistled across the savannah as a man of one hundred and fifty emerged slowly from the dust. Oh my, Tom gasped. It’s so hot. It’s so hot! Is it normally this hot??

Karibu, welcome, the man spoke wearily. We followed him into a small hut, paid our dues and waited expectantly for the tour…a tour which illuminated little more than the fact that Homo Erectus fashioned an awful lot of hand axes half a million years ago, in a place that is jolly hot. This is a hand axe, the man pointed out. This is another hand axe. This, too is a hand axe. That there is a big hand axe. All those there are hand axes. Would you like to see the elephant’s skull?

Tom and I practically ran to the car. Tom grabbed the key off me, threw himself into the driver’s seat, hit the ignition and skidded across the gravel back onto the main (i.e. only) road as I chased after him. No more stop offs! He warned. It was 11am. I was roasting.

It took a further two hours to reach Magadi: progress was slowed by hitching Maasai. Matatus don’t ply this route often, and the locals rely on catching lifts with passing cars (not many wazungu though, judging by their faces each time the car slowed and realisation hit). When we slowed for one couple, giving them view of the two empty benches in the back, they cried out to a tree and a flood of people came running to the car and clambered in. I counted six women, five men and three babies. Tom drove on with me turned 180 degrees, grinning inanely at the crowd as the crowd grinned back at me.

That was the highlight. For Magadi is possibly the most depressing town in Kenya. The Madadi Soda Company has made it home on account of the lake’s soda content, which enables the extraction of sodiums chloride and carbonate; and like Robert Owen at New Lanark two hundred and twenty five years earlier, has built staff accommodation, a school, a restaurant and a recreation hall. For how else could you get people to live here, in the 45 degree heat?

We acquired two ‘guides’: young men who had no useful knowledge beyond which direction to drive between the acacia trees to reach what they promised would be spectacular: a large pond. This is NOT it, Tom warned. I have NOT driven three hours OFF ROAD to see a POND. Upon our silent return across the water, they inexplicably informed us that we were now driving across Lake Magadi. It brought to mind David F Horrobin’s warning in A guide to Kenya and Northern Tanzania (1971): ‘Magadi causeway is worth driving along just to get an impression of what hell must be like’.

Finally, we were persuaded to drive a further fifty minutes to ‘the healing hot springs’, to discover a shallow pool. But Tom had been promised hot springs, and Tom was on a mission. He stripped off, sat in the pool and refused to move, multi-coloured and cross.

After some time and much cajoling, I got him back into the car, and we dumped our guides on the roadside. By now it was getting dark, but the heat refused to abate. We drove back to Nariobi, climbing for hours back up the Rift Valley and stopping only at a roadside duka for water. Like something from Wolf Creek, a man suddenly rapped on the driver’s window while I was waiting for Tom. Aaaaaaargh!! I screamed at his white eyes in the dark. Luckily, he was just drunk, not murderous. Which is more than I can say for Tom…

Going West: a work jaunt

The NGO where I work has offices in Western Kenya. Western Kenya has one of the highest rates of HIV in the country. It is also, promised the guide book, ‘virtually untouched by foreign tourists’. I turned to my colleague Ruth: Let’s do some travelling after work. It’ll be fun!

Things went surprisingly well for the most part. We walked in the last remaining patch of the Guineo-Congolian rainforest at Kakamega; we looked out at Lake Victoria, the second largest freshwater lake in the world, from a rooftop bar in Kisumu city; and we explored the countryside on the route to Uganda. We travelled by ‘road’ (the fact that this was the only bus in Kenya which departs with the back seat empty should have been indication enough of the terrain; the safety handrail came off in my hands during a particularly vigorous stretch) to visit ‘the tiny and rarely visited’ Rusinga and Mfangano Islands, where we wangled three nights in a luxury lodge retailing at $550 per person per night but now being let go for the price of a Bristol Travelodge by a woman who wept over the phone. Not only did we have it to ourselves, we also negotiated free transport in a luxury open-sided jeep, from which I waved magnanimously like some colonial horror to everyone who disinterestedly looked our way.

But it didn’t all go smoothly. Keen to visit Saiwa Swamp Park (‘small and rarely visited’), we attempted the journey in one day from Kakamega: 100km, two matatus and a taxi away. Turns out that just because something is two thumbs away on a map, doesn’t make it close. And that the unpredictability of Kenya’s matatu system increases exponentially in relation to its distance from Nairobi. The journey started ignominiously when the entire sliding door to our matatu fell off while travelling full pelt. Rather than express alarm that a pedestrian might have been felled by the flying hunk of metal, or a passenger fallen out onto the street so tightly were we packed in, the driver was cross; cross in a way which made me think this was not the first time. And quick to somehow jam the door back on with a speed which confirmed my suspicions.

The next matatu stopped in the middle of nowhere, in the dark, halfway to our destination of Kitale. Saying something about there being too few passengers to be worthwhile, the driver harrassed nine of us, luggage and all, into a beaten up car, where we travelled the final 30km with the vehicle’s innards scraping the ground, stopping only at a Police checkpoint (Uh-oh, we’re done for, I thought, as the policeman rapped on the window and, very slowly and deliberately, asked: What are you DOING in here? This is terrible! You must be so uncomfortable! How did you let them put you in here like this?, ignoring our protestations that we were fine. It’s bad, the car driver muttered when we started again, shaking his head – We paid him off on the way).

Our plan was thwarted by the taxi driver not having a clue where Saiwa was and driving for two hours in the dark (the later it got and deeper we drove into the countryside, the more people refused to approach a strange man in a strange car), and the announcement, tardily made, that we were almost out of petrol and possibly worse. The car made it to the outskirts of Kitale, where it lurched onto a petrol forecourt and conked out. Ruth and I gathered a small crowd, wondering at the wazungu out on the streets at 11pm near a small agricultural town.

The car having miraculously started again, we drove for a further thirty minutes looking for the only guest house which answered the phone, enduring another altercation with the police (The people in these houses rang us. They say a strange car is going to rob them) before pleading for the guest house owners to fetch us; the gleaming 4×4, friendly faces and two dishes of leftover takeaway lifted our spirits no end.

The next day, we tried again for Saiwa Swamp. I’d like to say it was all worth it. But after walking about for a bit with a Boy Guide in flip flops and tracksuit trousers and stopping off on the way back to the guest house at a farm for deformed animals (a bull with three eyes and four horns, lots of three-legged things; floppy cows, floppy sheep, floppy cocks, floppy chicks…), I was rather glad to be back in busy, polluted Nairobi the next day…

Lake Turkana and the North: I don’t think we’re in Kansas any more, Toto

Despite northern Kenya being truly off the beaten track (the distance from ‘civilisation’, the lack of roads and the inhospitable terrain), I’m not sure that our methods of getting there count as such. I hang my head in shame and declare: it was an organised safari. Upon arrival at the famed Lake Turkana, the largest permanent desert lake in the world, my fantastic recreation of Count Teleki’s 1888 journey to the Jade Sea – the first European to see it after an arduous safari across Eastern Africa – was interrupted by twelve Israelis descending upon the campsite. The differences between myself and the Austrian explorer seemed even more stark when a wizened Brit staggered over to us, having walked 40km across the Chalbi desert to reach the mythical lake; I looked across at our pimped-up Toyota Land Cruiser in dismay, consoling myself that at least I wasn’t an Israeli in a truck.

Despite northern Kenya being truly off the beaten track (the distance from ‘civilisation’, the lack of roads and the inhospitable terrain), I’m not sure that our methods of getting there count as such. I hang my head in shame and declare: it was an organised safari. Upon arrival at the famed Lake Turkana, the largest permanent desert lake in the world, my fantastic recreation of Count Teleki’s 1888 journey to the Jade Sea – the first European to see it after an arduous safari across Eastern Africa – was interrupted by twelve Israelis descending upon the campsite. The differences between myself and the Austrian explorer seemed even more stark when a wizened Brit staggered over to us, having walked 40km across the Chalbi desert to reach the mythical lake; I looked across at our pimped-up Toyota Land Cruiser in dismay, consoling myself that at least I wasn’t an Israeli in a truck.

In our defence, we had only ten days to travel 1800km and had been warned about tribes indulging in cattle rustling who, while not directly interested in cow-less tourists, sometimes like to fire warning shots in their direction. Hiring a driver and a cook was the only option when you have a mother like mine.

But I promise, things still went wrong. Our driver was a borderline alcoholic (no one likes to smell morning whiskey on the breath of someone who is about to drive four hours across a narrow mountain road) who was surprisingly functional until the last two days, when he inexplicably fell apart. He couldn’t be roused for our morning bird walk, kept on asking us the same question and climbed into the tent of our two Belgian companions in the middle of the night, pleading that he ‘just wanted a cuddle’. Our cook was a dour-faced mute whose inner thoughts we constantly tried to guess (Fine-tuning the denouement of his novella? Attempting to deconstruct beauty?)

Part of northern Kenya’s delight is also its difficulty. From deserts to mountains, forests and volcanoes; in other words, from scorching hot to freezing cold, to pouring with rain, to the-chef-and-his-tent-blown-away-in-a-midnight-windstorm (1987’s got nothing on this, Michael Fish): all connected by terrible roads. A rainstorm in the Samburu Valley forced us to seek refuge for the night in the house of a Northern Irish missionary, who regaled us with tales of vandalism and shootings (two attempts in 23 years ain’t bad), before we traversed the world’s worst road (four hours to travel 100km across rocks) to Maralal town.

And some things are off the beaten track for a reason. Take a safari in Marsabit National Park: a dried up lake inaptly named ’Paradise’, a few baboons and a dead elephant. The KWS ranger also assured us that crows live to 300, which indicates the requisite level of training for this posting.

As we entered cattle-rustling territory south of Turkana, two armed guards climbed into the vehicle behind us. Driving ‘in convoy’ meant waving the other car off in the morning, roaring away and meeting up again at nightfall. When we finally got our own askari, our only thought when we saw the ancient man trotting towards us with a toothless grin was – let’s hope he lasts the journey (of course we were proved wrong; he turned out to be incredibly helpful and cheery). I spent much of the journey to Tuum looking down the barrel of his Kalashnikov. Don’t worry, said our driver reassuringly, he probably doesn’t know how to shoot it. I eventually pushed it away, aiming it at the cook’s face instead, which made me feel much better. But not as good as a really hot shower and clean clothes felt after ten nights in a tent.

So what?

Sometimes, when I’m erecting my tent in a thunderstorm, my only pair of socks soaked through and no shelter, I think about a package tour to the Maasai Mara, relaxing on Diani beach or reading the papers in Java coffee shop on a Sunday morning. And I will do all those things (for what better angle from which to scorn than the knowing one?). But would I choose them over Kalacha, where ‘the sense of isolation is magnificent’? Over North Horr, which has attained ‘a mythical status akin to Timbuktu’ given its sudden appearance out of the relentless desert? Over Ruma National Park, where you will experience ‘utter seclusion all to yourself’? Not a chance. And if things go wrong, it’s all part of the adventure. All I can say is: Tom, Ruth, Taz, everyone – We’ll laugh about this one day…

Posted in bribes, lakes, masaai, matatus, mzungu | 3 Comments »

More than 1.5 million people in Kenya are living with HIV/AIDS. 3 out of 5 HIV-infected Kenyans are female. 1.2 million Kenyan children have been orphaned by AIDS. Some areas of Western Kenya have infection rates of 30%…

Everyone in the West knows something about HIV/AIDS. Everyone knows roughly how it is transmitted, and that there is no cure. Everyone knows that it affects Africa disproportionately. Most people, I’d guess, are terrified of it. But most think it won’t happen to them; not where they come from.

And they’re right – it probably won’t. So when they read statistics about the scale and impact of HIV/AIDS, they might think how awful it is, but move on. HIV/AIDS, like famines, war and tribal conflict, has somehow come to characterise the ‘Dark Continent’. Many of the positive stories coming out of Africa never reach the West, so people see the continent as forever blighted, unchanging and unchangeable – and who can blame them for switching off?

But what happens when you are forced to confront HIV/AIDS? When you live in a country where 6.3% of the population are estimated to have the virus? Where, although the prevalence rate has halved from its peak in 2000, HIV/AIDS is still considered the most significant non-political threat to that country’s development?

Not only am I living in a country where HIV/AIDS is a huge issue, I work at an NGO which provides treatment and support to those affected by it, and whose requisite for employment used to be having HIV rather than skills. Before moving to Kenya, I had never knowingly come into contact with someone who has HIV/AIDS. During my previous travels in East Africa, I had a notion that statistically, it was likely that some people I came in contact with had it – but it wasn’t something I was conscious of. I’d never talked to anyone about having HIV, and had never had a relationship of any kind with someone with it, be it friend, acquaintance or colleague.

But now, I work with some incredible people who have stood up and openly declared themselves to be HIV positive, when probably the normal – and safest – reaction would have been to keep their heads down, take the drugs and not talk about it publicly. They introduce themselves as HIV positive. They discuss it openly. They take their pills while talking to me over chai. But most importantly, they look completely healthy and have energy, enthusiasm and successful careers. They tell people because they want to set an example (our Executive Director has been HIV positive for 20 years, and seems fit as a fiddle), and they want to educate people. Most days I forget that the majority of my colleagues have a life-threatening condition.

There are a lot of stories about HIV/AIDS activists, but what is often forgotten is the very real and personal decisions they made and the sacrifices these came with. If I was diagnosed with HIV, I’m not sure I would be brave enough to openly declare it, despite the positive publicity that it might bring to fighting the disease. For now, I’m proud to be working for an NGO dedicated to fighting the cause, where I can learn from people who are open about their status.

So is this a sign of how far things have come in Kenya? Have negative attitudes declined to the extent that people feel comfortable disclosing their status? Has access to healthcare increased? Or have things only improved for the educated, those who know their rights and how to fight for them?

I wanted someone with HIV to give me their view. I asked Teresia. Teresia is a counsellor and an advocate for both maternal and new born child health, and for women’s rights, and has worked with policy makers in Kenya, South Africa and Washington D.C. She’s also my favourite colleague.

Teresia

In 2002, Teresia started feeling weak and coughing. She was diagnosed with Tuberculosis and doctors recommended she take an HIV test. TB is an ‘Opportunistic Infection’: it is OIs such as this and pneumonia which kill those with HIV/AIDS: 50% of people with TB in Kenya are estimated to have HIV.

Teresia tested HIV positive, with a CD4 count of 10 (HIV attacks these CD4s, a type of white blood cell). This was shocking, given that a healthy person normally has a CD4 count of around 1000-1500, and she was hospitalised. Her husband, after a ‘false positive’, tested HIV negative.

She was put on TB medication for two months, but not ARV (Anti-Retroviral – HIV) treatment, for several reasons. Firstly, if a patient has not yet started ARVs, they must finish the course of TB medication. Secondly, ARVs were not readily available in 2002, only found in private clinics at a cost of KSH60,000 a month [around £430]: prohibitively expensive to most people in Kenya. Thirdly, free ARVs were only given to people on ‘programs’, especially the Preventing Mother to Child Transmission program. Although Teresia had a one year old son, she was not pregnant, so didn’t qualify for help.

She was finally able to start ARVs at the end of 2003, when the Government had subsidised them: KSH3,500 a month [£25] was a price her husband could afford. Today, Teresia takes three pills in the morning and four in the evening. She’s now on her ninth year on medication and feels perfectly healthy, with no side effects from her current drugs. She attends ‘clinic day’ every two months to collect more ARVs, and has a CD4 count test every six months.

Progress

Teresia thinks Kenya has come far in HIV treatment since she was diagnosed. In 2002, treatment was only offered in private and main Government clinics; now, almost every health centre and most communities in rural areas have access to it. The amount of funding that has come into Kenya, mostly from foreign donors, has meant that a huge – some would say parallel – health system for those living with HIV/AIDS has been constructed, which the Government has recently said it wishes to integrate into mainstream healthcare. The price of ARVs has reduced from KSH60,000 a month to 3,500, then 500, and now nothing, which has resulted in a 29% decrease in the number of AIDS deaths over the last seven years. There are still costs involved, though, which makes diagnosis and treatment prohibitive for many – the HIV test costs KSH1,500 [£12] in some areas, and liver function tests cost around KSH2,000. In some areas, testing equipment is not even available, and diagnosis is done by clinical monitoring.

But a major problem, Teresia fears, is access to food. HIV/AIDS often makes people nauseous and therefore less likely to eat food, yet it increases the number of calories they need and therefore makes them hungry. Food prices have rocketed in the last few months, making it very difficult for some to eat a balanced diet. If those with HIV/AIDS don’t get the nutrients they need, they feel hungry and weak and stop taking their ARVs. If they stop, they might not be able restart the same drugs, and might therefore have to progress onto ‘second line’ treatment, which restricts the diet even more and is more expensive. Resistance to ARVs is one of the biggest worries facing countries like Kenya, where many people should be moved to ‘second line’, but the country cannot afford it. Teresia feels lucky that she can afford three meals a day, and is still on ‘first line’ treatment, but is well aware that many cannot.

Stigma

But on to one of the aspects of HIV/AIDS in Kenya which confuses me most. In a country where the prevalence is so high, where almost every city suburb has a purple ‘VCT’ sign announcing Voluntary Counselling and Testing, and where almost every rural community centre has HIV/AIDS campaign posters plastered over its walls – in short, in a country where no one can truly say they are untouched by the virus – stigma and discrimination towards those living with HIV/AIDS is still rife.

Teresia says that back in 2002, stigma was terrible. Many HIV positive women were disinherited of their matrimonial property and their rights violated. Teresia didn’t reveal her own status for a long time: she only felt able to tell her sister three years after knowing, and her other sister and some friends later.

Neither did she tell anyone in her religion – she is a Jehovah’s Witness – at first. The people she eventually confided in were ‘generally’ supportive, although some told others who wouldn’t even greet her. She finally told the elders, who now send to her people whom they suspect of having HIV. (Interestingly, Teresia claims her faith never wavered. In fact, she believes it was faith that made her survive with HIV for such a long time, and she feels she has even more reason to trust in God).

Things are very different for Teresia now – she feels able to tell people that she’s HIV positive. But perhaps she is able to do this because of the support she gets from our organisation, from her husband (whom she gave the option of divorcing, but he refused), and from her friends and family. She is also educated and both she and her husband bring in money.

But what about other people living with and affected by HIV/AIDS? People who don’t have such supportive and understanding networks, and people who are not as educated, don’t have an income and don’t have access to information?

Teresia agrees that stigma is still bad, particularly in rural areas, where there is less education, despite 70% of infections being found there. In Sega, Western province, there is a tradition of women cooking at funerals. HIV positive women are not allowed to participate in this activity because of fears that their sweat will fall into the food and transmit the virus. If a woman is not involved in social activities like this, she is ostracised from her community.

Still in Kenya, widows are often blamed for their husbands’ deaths, even though you can bet it was the husband who contracted the virus from someone else. A young woman came to the office one day, having been thrown out of the house by her stepmother when she revealed she had the virus. There is the belief that a HIV positive woman should not give birth: attending various training sessions for work, I’ve learnt that health workers can be judgemental of women who are HIV positive and pregnant. Children, too, are punished. A friend explained how her sister died of AIDS, leaving behind an HIV positive little girl. My friend informed the school of her status, and later discovered that the teachers were either avoiding her or verbally abusing her, and the children were encouraged to taunt her. She withdrew her niece and enrolled her in another school – where her status remains undisclosed.

Increased access to HIV treatment has seen people with HIV/AIDS rise up from their deathbeds to become healthy, productive citizens; the Government has been taking the epidemic seriously in recent years; and key institutions like the Church are now involved in the fight (the Evangelical Alliance of Kenya is even running a Most-At-Risk-Person’s programme that targets sex workers and men who have sex with men) – and yet, although research has shown these approaches reduce stigma, it still remains. Why is something that seems to be so much the norm still so much feared, and why are those that have it still labelled and discriminated against? Why is something that no longer causes widespread death still seen as taboo?

One reason could be fear: of a virus that strikes people in their prime; a disease that many still believe to be a death sentence. Another is cultural. Because it is mainly transmitted sexually, HIV/AIDS brings up issues of sex and morality in a conservative country. People living with it are often seen as shameful, and the virus seen as ‘punishment’ for amoral behaviours. Also, perhaps it still carries stigma because it is a symbol of disorder; the latest in a long line of things that have created social upheaval and suppressed the continent.

Then again, why should stigma disappear overnight? HIV/AIDS is a relatively new disease, the Government has only formally acknowledged it for the last twenty years, and people with the virus have only started living full lives in the last ten. This, bound up with the complex cultural reasons for stigma and the fact that it really is a frightening disease if left untreated, means that stigma will take time to disappear. But people are hopeful. One doctor told me she believes that in future, HIV/AIDS will be seen as a manageable condition, like diabetes, with no more negative attitudes to the patient than accompany that disease.

What does the future look like?

The issues of stigma, access to food and drug resistance are pressing in Kenya. But there is also the issue of funding. Teresia fears that Kenya is sitting on a time bomb, due to its reliance on ever-decreasing donor funding. Global Fund and PEPFAR (USAID) currently fund 90% of ARVs in Kenya, but this is unsustainable. The Kenyan Government must act now, Teresia says, to invest in medication: while 400,000 people are on ARVs, a further 420,000 are on the waiting list – and this doesn’t account for those who have not accessed services, or even been tested.

Teresia thinks the Government also needs to change its strategy on the prevention message, to change peoples’ behaviour and stop new infections. She is counselling people who tested negative last year and were given plenty of information, but this year have contracted HIV, and she cannot understand why this is happening.

Teresia says that personal determination to fight stigma and motivation to live for her child kept her going when she was diagnosed. Now, ten years on, she is passionate about bringing change: increasing access to HIV treatment and fighting to end new infections, stigma, discrimination and violation of rights. We in the West should support her in that.

Sources:

http://www.avert.org/hiv-aids-kenya.htm

International Monetary Fund, Kenya: Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper, July 2010

Kenya National AIDS Control Council, Kenya Analysis of HIV Prevention Response and Modes of HIV Transmission Study, 2009

Kenya National HIV and AIDS National Strategic Plan for 2009/10–2012/13

UNAIDS, Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic, 2010

UNGASS, Country Report: Kenya, 2008

Posted in HIV/AIDS | 4 Comments »

June 1, 1963 (Madaraka, or internal self-government, day):

‘As we participate in the pomp and circumstance, remember this: we are relaxing before the tall that is to come. We must work harder to fight our enemies – ignorance, sickness and poverty. Therefore give you the call HARAMBEE. Let us all work harder together for our country Kenya.’ (Jomo Kenyatta, Kenya’s first President)

June 28, 2011 (Tuesday):

‘My friend John is getting married. Please will you be the Guest of Honour at his Harambee?’ (Teresa, cook)

————

I was in a small church somewhere in Eastern Nairobi. A young man with a microphone was calling members of the congregation up to the altar in turn. One by one they would walk down the aisle, make a speech and present an envelope to the man. The church would fall silent as he opened it and removed a wad of money. The total amount would be announced, with fanfare, to the congregation. True theatrics were reserved for two men and two women seated on the altar, who each handed over ‘not one thousand Kenya Shillings, not two thousand, not five thousand, but TEN THOUSAND SHILLINGS!’ After each donation, the audience would cheer, and the man would entreaty them to top it up by 20%. Obliging members would walk up to ‘boost’ the original transactor by depositing a few hundred shillings into a wicker money pot claiming centre stage on a stool. Soon, my name was called…

For I was at a pre-wedding fundraiser, under the guise of that famous Kenyan institution: the Harambee.

‘Harambee’ (har-AM-bay), the official motto of Kenya, is both a concept and a call to action. A Kiswahili word meaning ‘let us all pull together’, its origins lie in the Indian railway men who, when heaving heavy loads of sleeper blocks and iron rails during the construction of the Lunatic Line, would chant ‘har, har, ambee!’ (praise, praise to Ambee mother – a Hindu deity). Kenya’s first president, Jomo Kenyatta, was said to have witnessed a railway line team and decided that it represented the metaphor he wanted for his new nation: a country working together in harmony, sharing its load.

(Some argue that Harambee has its origins in the Bantu word halambee, a compound noun made up of two words, hala and mbee, meaning ‘put effort’ and ‘go forward’ – but where’s the story in that?)

The Harambee embodies ideas of community and self-reliance. While this concept has a strong history in East Africa, with many communities forming self-help groups, it was at independence in 1963 that it really gained momentum in Kenya. For, in order to translate the optimism of the people into benefits, Kenyatta’s government sought rapid economic and social development, using Harambee as an informal development strategy to achieve this. Kenyatta encouraged communities to work together to raise funds for local projects, promising that the Government would provide additional manpower, materials and funding. Guided by the idea of collective good rather than individual gain, Harambee projects saw the construction of schools, health facilities and water projects.

Happy Harambee?

The Harambee movement has played a key role in Kenya’s rural development – but it has not been without problems. Most controversially, Harambee fundraising events have been subject to political manipulation: wealthy individuals wishing to get into politics could, and do, donate large amounts of money to local Harambees, thereby gaining legitimacy.

In an attempt to curb this corruption, the Public Officer Ethics Act 2003 states that it is illegal for public officers to organize or preside over Harambees, or to be listed as guests on Harambee cards. Yet the potential for corruption has not abated; as an MP, Angwenyi, debated in Parliament just a few years ago: ‘As we have come to learn, Harambee is a very inefficient method of developing our country…it encourages corruption. I know, if you want to conduct a Harambee to build a hospital or a dispensary for needy people…and you come to me and I give you KSH1 million which would complete that dispensary, it would be very difficult to prosecute me, even if I committed a crime and came before you! That is because you will be thinking about the people that I have helped in your constituency.’ (Not that this doesn’t work both ways, of course. In the run up to the 2012 General Election, churches, schools and women’s groups have been accused of playing dirty by inviting politicians to Harambees, assuring them that they are the key attendee, only to invite opponents later. If the politicians do not attend, and donate big, they will automatically lose votes.)

The (mis)appropriation of Harambee

But what does mobilising a rural community to fund and build a school have to do with my presence at a church in Nairobi, giving money to a man about to get married? Quite. For, aware of the benefits to be reaped from the Harambee, savvy Kenyans have shifted its meaning from focusing on projects for the collective good, to fundraising events aimed at helping individuals. Your father’s hospital bill needs to be paid, your daughter wants to go to university, your cousin has died… whatever the money needed, a ‘Harambee’ will invariably be held or a ‘Harambee fundraising form’ distributed. Although a Harambee was always much more than a fundraising event, this is what it’s now best known as. Many people think long and hard about which Harambees they attend. Hospital bills, funeral costs and education fees are deserving, but if you want to raise money for ‘leisure’ purposes – such as your wedding or even to study abroad – you won’t get many people willing to part with their hard-earned cash.

Of course, we in the West love to hold fundraising events. But normally, we give something in return (a movie night, a party, Celeste’s special cakes) or require something to be done by the recipient (run a marathon, cycle to Brighton, climb Kilimanjaro). Neither do we badge it as anything other than ‘fundraising for charity’. So I was curious to see how the concept of Harambee, with its loaded history and meaning, translated into an individual’s money-making efforts – and who would actually turn out to fund someone else’s wedding. And so, in the name of research and self-interest (never get on the wrong side of the office cook), my colleague Ruth and I accepted Teresa’s plea to attend her friend’s Harambee (after requesting that we be demoted from ‘Guests of Honour’ after her estimate of our expected contribution)…

The main event

John is getting married in August and wanted to raise money to pay for it. An individual is only really allowed to hold one Harambee in their lifetime – so he needed to make it a good one. We arrived at his church at the stipulated 2pm. He decided to maximise profits by forgoing renting a hall and instead relying on the goodwill of the vicar, who offered the church for free. Backing music was provided by the church band. The audience (a not-too-shabby 50-strong, especially given the fact that it classified as a ‘leisure’ Harambee) was comprised mainly relatives and friends of the groom, from the church. The four people seated at the high table on the altar were the Guests of Honour; leaders of the community, heavy with the weight of expectation and anticipating nothing immediately material in return for their donations except ‘feeling good’, and the status that undoubtedly comes from being a ‘big man’.

One and a half hours later, festivities were kicked off by the compere (the young volunteer with microphone). Although ‘festivities’ is perhaps overselling it; for, apart from a random interlude of three women modeling up and down the holy aisle in business clothes and a group of youths performing a short dance, the whole three hours was dedicated to one thing and one thing only: MONEY MAKING.

For here began the ritual of calling people up one by one. When that got boring, the compere summoned the hitherto-unseen bride. Look at her! He cried. She needs to buy clothes, and shoes, and new hair! Who will help her buy new hair? At which all her friends walked up and tucked money behind her ears. And then it got boring again, as we settled back into call person/give speech/donate/cheer/top up by 20%.

And that wasn’t all the money expected. I counted no less than five opportunities to extract money from me, in addition to my ‘donation’. Upon entrance, I was forced to buy a handkerchief for KSH100. I had to tell the audience my name, and pay KSH50 for the privilege (or, the compere winked, if you don’t want to say your name, give me KSH100). I was hungry and thirsty (Kenyans expect food wherever they go) but had to buy overpriced sodas, samosas and chapatis. I was sold a raffle ticket, hoping I wouldn’t win the own-brand cellular phone. And that’s not to mention the 20% top-ups and the periodic counting and entreaties for more.

John raised a total of KSH100,075 (around £738). I was torn about what I thought of the whole thing. On the one hand, the tedium and unabashed purpose for gathering everyone together, combined with the refusal to provide anything in return (those models and dancers DON’T count), made me feel uncomfortable. Why were we all supplementing his wedding? Why doesn’t he hold a smaller wedding that he can afford? (Many Kenyan friends expressed indignation at this and claimed there’s no way they would have accepted that invitation). What about the pressure on members of the community who couldn’t afford to be topping up his luxuries? Would they have felt ostracized for not attending? Cheap, even? I saw one woman surreptitiously add another KSH1000 to her envelope when she saw what others were contributing – did she feel bad for her original contribution, presumably based on what she could afford, and was she mentally making trade-offs for the lost money?

But on the other hand, it was a great day and showed the spirit and generosity of John’s community. His friends, family and neighbours were rallying around to help their friend when he had asked, showing solidarity and support. Everyone worked for free – playing music, compering, making samosas, manning the raffle stand – and seemed to have a great time together. The local men of standing, including vicars and youth group leaders, performed a real role in the day, agreeing to act as Guests of Honour. John and his bride needed assistance and their community came out with open wallets in support.

Everyone donated what they could afford (and sometimes possibly more), and the response was always cheers, no matter the sum. No one was made to feel bad at their contribution, and everyone felt the gratitude of the couple. It made me wonder how generous these people would be if the Harambee had been for something more ‘worthy’: paying hospital bills, for example. And for John, perhaps a Harambee was the only viable means of raising money for his wedding. Kenyans are expected to have big weddings, and feed all their guests – I’ve been to a few now, and the queues at the buffet tent are something to behold. In a country like Kenya, saving up to feed 400 expectant guests would take a long time, and acquiring loans is difficult. So although John’s Harambee was all about money making, maybe it was the only way he could have done it.

Ruth and I were panicking about our contribution – despite never having met John before, the compere was building up ‘our friends all the way from abroad!’ – but agreed we’d go up together and donate KSH5,000 (around £40). When we walked back to our seats, we saw tears in Teresa’s eyes. I convinced myself they were of pride rather than humiliation. John rang us the next day to give thanks for our donation and to invite us to his wedding (where I shall claw back my investment in chapatis). And I DID get an extra large portion of chicken on Monday…

Susan Njeri Chieni, The Harambee Movement in Kenya: the role played by Kenyans and the Government in the provision of education and other social services, Moi University

Chris Southgate and David Hulme, Environmental Management in Kenya’s arid and semi-arid lands: an overview (February, 1996)

‘Kenya National Assembly Official Record’, Hansard (July 18, 1973, December 1, 1994, March 20, 2003)

‘Politicians in dilemma over outlawed Harambees’, The Standard on Sunday, July 23, 2011

Posted in railway | 2 Comments »